Original Post by Tech in Asia

Written by Ridzki Syahputera

Life for Indonesian consumers is getting more comfortable amid an acquisition war between e-money players Go-Pay (backed by Go-Jek) and Ovo (backed by Grab and Tokopedia). It’s almost as if the two players are divorcees fighting over the custody of their children – consumers, in this case.

Consumers are taking full advantage of the situation, raking in every cashback, discount, and promo that Go-Pay and Ovo have to offer. Fifty percent cash back on bubble tea? Yes, please. A cab ride for 1 rupiah (US$0.000071)? I’ll take that too. What a time to be alive!

But in all seriousness, both players are bleeding copious pools of cash, and there seems to be no end in sight for this payments war. How long can they keep this up? Well, I’ll be the first to admit that their heavily subsidized user acquisition strategy doesn’t seem sustainable.

A race to the bottom?

There aren’t any published figures on Go-Pay and Ovo’s total subsidies, so let’s take a wild guess.

Of the millions of orders that Go-Jek and Grab process daily, perhaps half are paid by digital wallets, and we’ll assume that they’re all subsidized. If the subsidy ranges from 4,000 rupiah (US$0.28) to 10,000 rupiah (US$0.71) per order, then Go-Jek – who claims to be doing 3 million orders per day – subsidizes up to 15 billion rupiah (US$1.06 million) a day or around US$365 million per year.

Photo credit: Go-Jek

Although both companies are capable of raising billions of dollars, these are still huge costs. If they are willing to spend so much money to acquire users, there must be an endgame that’s significantly more lucrative.

Some anticipate that super apps Grab and Go-Jek will continue to duke it out over discounts until one’s war chest runs out. The sole survivor will then gradually reduce its subsidies to make the unit economics work. This strategy would work for the player with more money to burn.

However, both players are already large enough to sustain even half-a-billion-dollar annual burn rates. I don’t think neither of them will leave the outcome of this war to chance.

Owning all your daily transactions

The answer to getting out of this subsidy rat race likely lies in the proliferation of e-money.

Both Go-Pay and Ovo are driving traffic to offline merchants through their various promos. Their super app patrons are also delivering online orders for offline services like ride-hailing and food delivery. What’s missing here is the connection back to the online world, closing the virtuous online-to-offline-to-online loop.

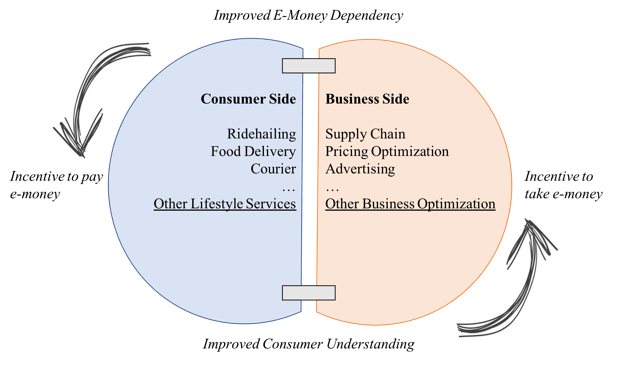

If the goal is to inevitably own the entirety of users’ daily transactions with more manageable subsidies, then another way to approach this is to boost users’ dependency on e-money.

In my case, I don’t put more than US$50 on e-wallets because it takes me a full week or so to burn through it. I’m only able to use it for transportation and meal delivery, plus spending at food and beverage stores. I use cash or debit card for the remaining bulk of my expenses: restaurants, bars, groceries, convenient stores, and entertainment – all of which don’t accept e-money.

If the majority of these expenses could be paid with e-money, I would certainly use e-wallets more simply because they’re more convenient.

Let’s take a look at China’s Alipay and WeChat Pay.

Alibaba and Tencent have invested heavily in offline retail. New or smart retail empowers offline outlets – from large-scale merchants to side-street mom and pop stores – by helping them to understand their customers better and optimizing their businesses.

These retailers gain invaluable data that fuels everything from hyper-targeted marketing to product assortment and even pricing optimization. Alibaba has a trove of purchasing behavior data, along with supply chain and logistical expertise, that directly support retailers. Meanwhile, Tencent understands the social media behavior of its users and indirectly acts as a tech layer for them.

(To learn more about how retail technology is shaping up in China, check outthis presentation by Connie Chan, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz.)

Ultimately, bringing the battle offline means that these super apps are able to monetize the merchant side of the business and capitalize on collected data while subsidizing their on-demand services.

In Indonesia, the merchant side of the online-to-offline (O2O) landscape is mostly facilitated from a payments perspective only. But there’s so much more value that can be provided.

Cash management and inventory management systems could be strong entry points, for example. Following the footsteps of Ling Shou Tong, Alibaba’s retail management platform, I can also see Indonesian e-money players offering supply chain services, pricing recommendations, and additional revenue streams such as advertising.

Players like Moka POS, Warung Pintar, and Ocean Going are already offering some of these services and could potentially act as strong partners for Go-Pay and Ovo to grow their footprint for offline merchants.

Once merchants realize the benefits of e-money, they can be incentivized to make it a preferred or the only available payment method. And we can already see this happening in China.

As more and more offline transactions get recorded online, super apps will harvest a rich database of daily consumption patterns that will translate into services offered to offline merchants. Consumers will eventually grow increasingly dependent as digital payments become ubiquitous, providing a consistent incentive to pay with e-money.

As this cycle iterates, super apps will eventually gain the ability to cut back their subsidies over time and improve their unit economics on the consumer side.

Again, this is not necessarily how things will play out but perhaps it does present an escape route from the endless subsidies. At the end of the day, this O2O cycle perpetuates the Alipay and WeChat Pay duopoly and is the driving force behind the US$12.8 trillion mobile payment market.

Although competition remains fierce between Alipay and WeChat Pay, it does show that e-money giants can co-exist sustainably – for the time being at least. I hope to see more constructive competition here in Indonesia as well.

Currency converted from Indonesian rupiah: US$1 = IDR 14,088